Our elders spoke of strange powerful things to come from the horizon in night and day, over the seas from the sky. The spirit of prophecy sang of white-skinned people coming out of the darkness to our land…

Until European arrived, Maori lived in a world peopled only by their spiritual beliefs, ancestors and themselves. At first they thought that these new arrivals were supernatural beings or ancestors that had come to visit their descendants. But they were white and strange in many ways. If they were neither supernatural beings, ancestors nor our people from Hawaikinui, then the world must be a different place from what we had supposed. As Maori thinkers reflected upon these matters, their understandings of the world and of themselves began to change.

Contact with European society for the Maori in New Zealand occurred well before Marsden became interested in setting up a mission in New Zealand. Frequent contact with European ships berthed to trade and take on supplies, while whaling ships called in for fresh provisions of food and water, loading up as well with whatever was available for trade.

Maori started visiting the European vessels examining the crew, guns and the physical lay-out of the ships, often staying on board all night. By and large Maori adopted a confident, entrepreneurial approach to the various European ships that arrived in their territory. They were eager to enter into exchanges with crews, and particular chiefs forged alliances with the leaders of successive expeditions to and from Aotearoa.

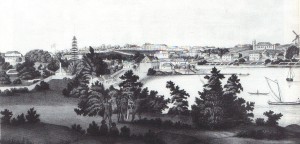

ARRIVAL OF MAORI IN SYDNEY 1811 – 1814

The time came when paths began to meet and relationships began to form and chiefs meet European alliances. As early as 1805, Māori were coming to Australia, such as Te Pahi, so regularly it was noted that “The Colony is never free from some of those Natives”. Another chief Kawiti Tiitua was perplexed and dissapointed by the general lack of engagement and hospitality offered by Europeans in Parramatta. He was anxious about what he could report back to his father, Chief Tara. The Europeans, he said, “have failed to recognise that I am a king at home”. He had not had the opportunity to learn anything useful, and had not accumulated gifts or wages.

In 1811 Paramount Māori Chief, Kawiti visited Rev Samuel Marsden at Ruatara’s farm at Rangihou, Parramatta. This visit by the Māori Chief Kawiti resulted in a section of land in the Field of Mars, being gifted to Māori Chief Kawiti. The Barramarragul Clan Leader marked a line across his land, cutting notches in the stumps of trees with a knife. When they asked him what he was doing, he replied saying that he was marking out a farm for Kawiti, who would return as soon as possible with one hundred men to work it. The problem with this gifting is Marden made claim to it, stating the following in his journal….‘I would give him as much land as he liked, and he might begin tomorrow’ a response worthy of a ‘rangatira’ Chief. Between Worlds, Anne Salmond pg 421.

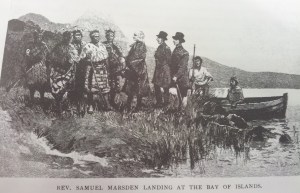

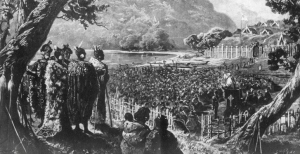

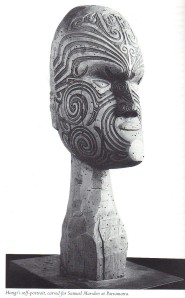

In 1814 it was considered safe to attempt to set up a mission station in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand. The Rev Samuel Marsden sent two missionaries, Kendall and Hall, to open communication with Maori Chief Ruatara and get the Maoris reaction to the missionaries living among them. They were well received by the Maoris, therefore on their return to Sydney, Marsden invited Maori Chiefs Ruatara, Hongi Hika, Korokoro and their families to come and live with him in Parramatta. The invitation was to stimulate trade practices and relationships, safe passage and protection for Europeans travelling to New Zealand, but more so dependency on the missionaries and European settlers. It was on this journey to Sydney that Hongi Hika carved the bust of his own head.

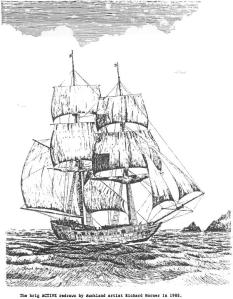

On the 22nd August 1814 the Active pulled into Sydney Cove.

The most documented relationship of all, was that of Hongi Hika and the Rev Samuel Marsden in New Zealand and later at Rangihou, Parramatta NSW Australia. Marsden was impressed by the intellectual capacity of the Maori he had met: Quote “Their minds appeared like a rich soil that had never been cultivated, and only wanted the proper means of improvement to render them fit to rank and civilized nations”. The fact that Maori ate people only convinced Marsden that Maori were in urgent need of salvation and preaching of the gospel.

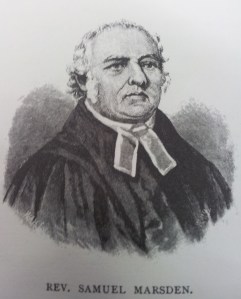

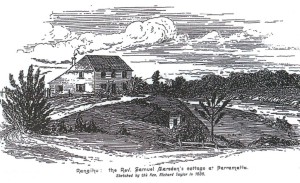

THE REVEREND SAMUEL MARSDEN

Samuel Marsden was a stong-minded Yorkshireman who had come to minister to the convicts of Port Jackson, now known as Sydney. After securing the post of assistant chaplain at Port Jackson, he settled in the colony where he became a magistrate, Principal Chaplain to successive governors, and a wealthy farmer. As a magistrate, Marsden became notorious for being the ‘flogging pastor’ when he meted out brutal floggings to Irish suspects during the 1800 convict uprising.

Marsden’s absorbing interest as a missioner was in the Maoris of New Zealand, whom he described to Rev. Josiah Pratt during his visit to London in 1808 as ‘a very superior people in point of mental capacity, requiring but the introduction of Commerce and the Arts, [which] having a natural tendency to inculcate industrious and moral habits, open a way for the introduction of the Gospel’. This English sojourn from early 1807 to May 1809 prepared the way for establishing the mission to the Maoris, in which enterprise Marsden displayed the qualities of courage, tenacity and resourcefulness that have made his name revered in New Zealand. Convinced from the first of the need to introduce industrious habits, Marsden engaged at his own initial expense craftsmen who were to return with him and teach the Maoris carpentry, shoemaking and ropemaking. His plans were interrupted by news of the massacre of the crew of the whaler Boyd at the Bay of Islands in 1809, but in 1813 he formed the New South Wales Society for Affording Protection to the Natives of the South Sea Islands and Promoting their Civilisation, and on 28 November 1814 set out with a party in the brig Active, which he had bought for £1400, to maintain the Maoris’ contact with civilization.

This was the first of Marsden’s seven voyages to New Zealand between 1814 and 1837. They yielded much in terms of self-realization but brought weighty problems of management, finance and discipline.

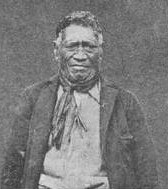

MAORI WARRIOR CHIEF HONGI HIKA

Maori Warrior Chief Hongi Hika was a Paramount Ngapuhi Chief in New Zealand, whose influence in Parramatta resulted in Trade, the Māori Seminary, the Declaration of Independence 1835, the Treaty of Waitangi 1840 and the Bible leaving Rangihou Parramatta, being incorporated into New Zealand and the NSW Settlers Parliament. In other words the laws in Aotearoa New Zealand came out of Parramatta as we know it today. This was the beginning of the Colonisation of European people in New Zealand.

Hongi was born at the very beginning of the European contact period. This was a time of late transition from bone, stone and wood age in Aotearoa to that of iron. Iron in those days was like gold today. It was the most coveted of salvage when ships ran aground. This time in history was significant as Maori were strategically positioning themselves for partnership with the European missionaries to ensure the survival of their people against other tribes in New Zealand. This meant that special relationships guaranteed access to guns and gunpowder.

“Hongi is a shrewd, thoughtful man, very superior to any other native I have yet seen. He is gentlemanly in his manners, and has ever proved the missionarys friend. I esteem him the greatest man that has ever lived in these islands. His name carries terror with it throughout the whole of New Zealand”. Rev Richard Davis.

Hongi Hika was considered of high ranking authority in society, and therefore introduced to King George IV. He received gifts of armor, as his status at this time, was recognised by the King and English of that of a ‘Māori King’. On Hongi Hika’s visit to England, Cambridge, he was further acknowledged for assisting Professor Samuel Lee with the compilation of the first Māori Grammar Dictionary. Below is Hongi Hika’s first attempt at writing the alphabet while in Ship Active, on voyage to Sydney in 1814.

Hongi Hika’s rise to power, knowledge of European trade, commerce, shrewd business sense and ability to negotiate for principal articles from the missionaries such as; muskets, axes, spades and hoes.

However in the background the NSW Settlers Parliament was planning to implement a government and steal Maori Lands from the tribal peoples of the lands. It was done through misleading translation of the treaty to the benefit of European settlers. However the Maori only aggreed to the following:

Recites Te Tiriti O Waitangi 1840 (Treaty of Waitangi 1840).

The Queen of England, preserved to Māori their independence, absolute sovereignty, power and control of their land herein this peace treaty. The agreement is to make a government for her people who are now in New Zealand and for those who will come in the future.

First: Māori give to the Queen of England the right to have a governor in New Zealand. Second: The Queen agrees that Māori keep their independence and keep control, full rangatiratanga [absolute sovereignty] of their lands, their villages and all their possessions, treasures. They give to the Queen the right to buy land, if they want to sell it.

Third: The Queen gives Māori people the same rights as British people.

Fourth Spoken promise: The Governor promises to protect Māori customs and the different religions in New Zealand.

Whereas signed by 512 Māori Chiefs; Recognised in International Law; and this treaty maintains Māori Authority in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Let it be known that Māori far outnumbered the European and were in control of the whole country.

Let it be known that Māori did not give their sovereignty to the Queen;

MAORI WARRIOR CHIEF RUATARA

Ruatara was a Ngapuhi Rangatira, tall man of commanding stature, great muscular strength and marked expression of counternance; his deportment was dignified and noble, appeared well calculated to give sanction to his authority, which the fire and animation of his eye might betray even to the ordinary beholder, the elevated rank he held amoung his people. His correct and unobtrusive manners which were not ony extremely proper, but well regulated, even polite, engaging and courteous.

Ruatara was a Ngapuhi Rangatira, tall man of commanding stature, great muscular strength and marked expression of counternance; his deportment was dignified and noble, appeared well calculated to give sanction to his authority, which the fire and animation of his eye might betray even to the ordinary beholder, the elevated rank he held amoung his people. His correct and unobtrusive manners which were not ony extremely proper, but well regulated, even polite, engaging and courteous.

Ruatara played a significant role in early relationships as Marsdens first major contact for the earliest of ventures. He was also Hongi Hikas nephew belonging to the Ngapuhi ariki’s (paramount chief) immediate family. Ruatara was to act as the protector for the missionaries at Rangihoua.

MAORI WARRIOR CHIEF KOROKORO

Korokoro a Ngapuhi Maori Chief of War from the opposite shore in the Bay of Islands, Ngaati Manu. He was very opposite to Hongi and Ruatara, an avid voyager and trader, but war was his only delight; and to this all his thoughts were turned with an inpatient avidity and wild enthusiasm that sometimes assumed the aspect of ungovernable violence. He never recounted the battles he fought or the foes he had conquered, without being transported with a kind of furious exultation; and when desired to sing the war-song and give a description of his mode of attack, his gestures and manner became outrageous to the very extreme of frenzy.

MAORI DOMINATION IN PARRAMATTA 1800 – 1840

The Rev Samuel Marsden often had Maori as guests in his house at Parramatta. Maori Domination was evident in Parramatta and Sydney during the early 1800’s as published by the Sydney Gazette journalists. Maori learned to speak English and the British sailors and traders learned to speak Maori. The trade ties were well established and very regular. Maori had grown accustomed to doing business with the British which also brought them prestige in New Zealand and enhanced their economic ties with Sydney traders. Ruatara – A Maori Chief of New Zealand, Anthony G Flude 2004

ABORIGINAL AND MAORI

The head of the Parramatta River was home to the Burramatta (or Burramattagal), a clan of the Darug people, whose name means eels (“burra”) and a place, usually a water place (“matta”), or ‘the place where eels lie down to breed’. Pre-European Parramatta would have been a place rich in a variety of food types and this combined with a warm temperate climate made it ideal for continuous settlement.

Māori expressed admiration for the Aboriginal people of Australia, their knowledge of that land, food gathering skills, fishing, throwing spear, the woomera and fighting abilities. There is no doubt each of the two groups, Māori and Darug, would have been very interested in the other; a Darug elder reports that his grand-uncle was called “Hongi” after the great chief Hongi Hika who spent some time at Parramatta.

Māori could not have avoided noticing that the displaced Darug people were at war with the colonial settlers, now under Governor Lachlan Macquarie. The Darug were officially referred to as “hostile natives” and were banned from carrying their weapons “within one mile” of any place “occupied by, or belonging to any British Subject.” Indeed, they were forbidden to come near even unarmed if they were in groups of six or more. As a result of witnessing the “terrible fate” of the Aboriginals at the hands of Europeans, Ruatara had serious misgivings about his settlers going to New Zealand. He later admitted that “he regretted, from his heart, the encouragement he had given [the settlers] to go to his country” because they would “shortly introduce a much greater number; and thus, in some time, become so powerful as to possess themselves of the whole island, and either destroy the natives, or reduce them to slavery”.

“THE FIRST NEW ZEALAND SCHOOL IN AUSTRALIA – THE MAORI SEMINARY PARRAMATTA 1815 – 1822”

The Rev Samuel Marsden decided to build a Rangihou Maori Seminary for the Sons of Maori Chiefs to teach them; European life; agriculture; blacksmithing; nail-making; brick making; cloth making; building; weaponary christianity; operation of the courthouse and church; planting wheat; managing livestock; wine making; fruit-growing and the English Language. The true reason for the seminary was to hold our children hostage so that the missionaries and government representatives sent to Rangihoua would be safe.

The Rev Samuel Marsden decided to build a Rangihou Maori Seminary for the Sons of Maori Chiefs to teach them; European life; agriculture; blacksmithing; nail-making; brick making; cloth making; building; weaponary christianity; operation of the courthouse and church; planting wheat; managing livestock; wine making; fruit-growing and the English Language. The true reason for the seminary was to hold our children hostage so that the missionaries and government representatives sent to Rangihoua would be safe.

The Maori Seminary ‘Rangihu’ (as it was first named) was not recorded on city plans until 1823 because the plans were designed to show the location allotments and buildings in the township of Parramatta, rather than Crown Grants such as the Rev Samuel Marsdens. The earliest record of the Seminary ‘Rangihu’ was drawn by Richard Taylor in 1836. In February 2005 Mr P Ngawaka of Te Whare Tangata O Rangihou succeeded in getting the remainder of Rangihou land permanently named ‘Rangihou Reserve’ under the Geographical Names Board of NSW.

The Rangihou Maori Seminary schooled up to 25 Maori students from 1815 to 1822. Most were from the region around the Bay of Islands and Hokianga, though some came from the Thames and Hauraki regions. From a European point of view, forming an Institution or a Seminary – that is a dedicated building, where clothes, food, work and instruction were provided – for Maori in Australia had become by 1815 a strategic necessity. To put it bluntly, the Europeans needed the Maori Chiefs to ensure a safe passage and protection for their people, to New Zealand as they had just settled in Ruatara and Hongi Hika’s terrritory in the Northern Bay of Islands. The Europeans were an isolated and possibly vulnerable group – especially because Ruatara, their friend who had lived at Parramatta, had died quite soon after their arrival.

The Seminary for New Zealanders in Parramatta remained separate from the Native Institution, although there was some later interaction between Māori and Aboriginal students. A relative of Hongi Hika lived with George Clarke and was in charge of the Native Institution when it was moved in 1822 to Black Town, thirteen miles from Parramatta. When William Hall, who had been a member of the first settlement at Rangihoua, took over the Black Town institution in 1826, a young Māori girl called “Kooley” [Kuri?] was at the school. Sadly, she died a short time after her arrival. A few young Māori, including “Toohee” [Tuhi], “Tupunah” [Tupuna] and “Thyka” [Taika] had accompanied W.Hall, living with his family and attending the Black Town Native Institution along with nine Aboriginal children. Ref 1; ibid, pp.205-209, 231.See also William Hall’s diary in Malcolm & Rosemary McLennan (eds), Son of Carlisle: Maori Missionary. The Diary of Missionary William Hall 1816-1838, Galston, NSW, Malcolm & Rosemary McLennan, 2001, pp.241-3. Ref 2;‘New South Wales’, in The Missionary Register15,1827, p.302.

SONS OF MAORI CHIEFS LIVING AT RANGIHOU 1819

Travelling to a foreign land, even into the care of a host, was perilous for Māori, who were not yet immune to European diseases or the consumption of foreign staple foods. By early 1822, thirteen of the sixteen young Māori who had been students at the Parramatta Seminary had died, some on passage to England, some on passage to New Zealand, some after returning to New Zealand, but four were buried in unknown and missing graves at Rangihou. There is no systematic record of these deaths, which are mentioned almost in passing in various letters and reports by Marsden. These included:

- PEREHIKO – Son of Chief Perehiko (Ngati Rangi, Ngati Manu, Ngati Hine)

Died and buried at Rangihou 1822

On being told of his son’s death Perehiko and his family sat in a circle on the deck of the Dromedary, and “the mat which the poor little boy had been accustomed to wear, and which was the only relic of him, was brought up and placed by “Iwi”, (Perehiko’s brother who had been in Parramatta) in the centre of the group. The scene of lamentation that ensued was truly distressing”. A musket, which had been purchased for him at Port Jackson, was laid before the elderly Perehiko, which “seemed to have some effect in restoring his composure”. Perehiko requested ‘utu’ – or a balancing payment – for the death of his son, and succeeded in getting quantities of goods from James Shepherd, a Wesleyan missionary based at Whangaroa, though Perehiko considered that James Shepherd himself should have been the payment for the boy’s demise. Shepherd to Butler, 4 August 1823, in R.J. Barton (ed.), Earliest New Zealand: The Journals and Correspondence of the Rev. John Butler, Masterton N.Z., Palomontain & Petherick, 1927, p.289. It is uncertain where the bones lie of those young chiefs who died at Parramatta, and not returned. They may be in some of the many unmarked graves in St John’s cemetery in Parramatta, but the relevant records have been destroyed.

- TENANA – Nepwhew to Chief Hongi Hika (Te Uri-o-Hua, Ngati Tautahi, Ngai Tawake)

Died and buried at Rangihou 1820

It was requested of Marsden that he send one of his own children to New Zealand to replace the one lost – to be adopted, and become a chief and to inherit land. Marsden’s Journal, 5 May 1820, in Elder (ed.), 1932, p.247.

- ATU – Son of Chief To Koki (Ngati Hine)

Died and buried at Rangihou 1822

When in June 1822 news arrived of the death of Te Koki’s son in Parramatta, Te Koki’s family requested that the particular part of the letter where the boy’s name was mentioned be pointed out to them: “with it they frequently touched noses; and prolonged for nearly two hours their incessant and melancholy lamentations for his untimely fate”. Marsden’s report,‘Affection of the Natives for their Children’, in The Missionary Register 10, 1822,p.391.

- TAUREA – Son of Chief Waiatarau (Ngare Hauata, Ngati Rangi)

Died and buried at Rangihou 1818

Waiatarau lost two sons, one at Parramatta and one soon after returning. “Taurau” and “Taurea”, two young men who had been at the Seminary for a year, whose “reasoning facilities are clear, and their comprehension quick” died of a fever on the Claudine in late 1818, in Batavia (now known as Jakarta), on their way to England. Marsden’s report,‘State and Prospects of the Mission, at the Time of Mr. Marsden’s Second Visit’, in The Missionary Register 8, 1820, pp.306-7.

In April 1822 it was decided that the high number of deaths of our high-born sons, the seminary was closed.

In later years the seminary burned down.

Today it is known that many of the children died from disease and murder. The bones of the some of these children were never sent home and still remain at Rangihou today.

FIRST MISSIONARY SCHOOL AT RANGIHOUA, IN NEW ZEALAND

Meanwhile, at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands, Thomas Kendall, the teacher Ruatara had asked for, had opened a schoolroom in 1816. Twenty-four Māori pupils aged between nine and twenty were marked as present on the roll on its first formal day of operation, 12th August 1816. This was the first school in New Zealand. The school’s focus – such as it was with children unused to the confinement of a classroom – was on reading and writing in Māori, as well as food-gathering and other chores. Kendall had made some progress in writing down the local Māori language (now known as Ngapuhi dialect), thanks to tutors such as Tuai, as well as Towhai, Te Pahi’s seventeen-year-old son, who was an assistant at the Rangihoua school.

HONGI HIKA VISITS THE KING IN ENGLAND

Marsden was opposed to Hongi leaving for England as Hongi was their principal protector. Hongi arrived in England on 8th August 1820. Experience of Maori tradition would have led Hongi and Waikato to expect a welcome on a grand scale, but there was no welcomers, no songs and no ceremony. Within days they were on their way to the University of Cambridge where an approved task awaited them. The trio (Hongi, Waikato and Kendall) came to reside in a street called Auckland. The Cambridge residents were somewhat startled at the sight of the two tattooed Maori chiefs in tribal regalia, the chiefs may have been equally astonished at the admixture of vagabond itinerants and rembunctious students. Professor Lee lost no time in introducing the chiefs to the Vice-Chancellor, Reverends, Professors and Baron de Thierry.

Hongi and Waikato contibuted to Kendall’s Maori Grammar and Maori pronunciation. There was no doubt that the compilation of the New Zealand Grammar Dictionary was an efficient and competent exercise. It was in print before Kendall left England, and over time helped to form a basis for written Maori. It was 230 pages long, 130 devoted to grammar and associated exercises and the remaining 100 constituting a dictionary. Hongi Hika later returned to New Zealand to continue his role as a paramount chief for his people.